This week, the federal government is putting forward a motion to pass its change—announced in the 2024 federal budget—in how capital gains are taxed. The feds are looking to change the inclusion rate for capital gains from 50 per cent to 66.6 per cent for every dollar one makes above $250,000 in annual profits. The change, which passed in a vote on June 11, will come into effect on June 25.

There seems to be total confusion about what this means.

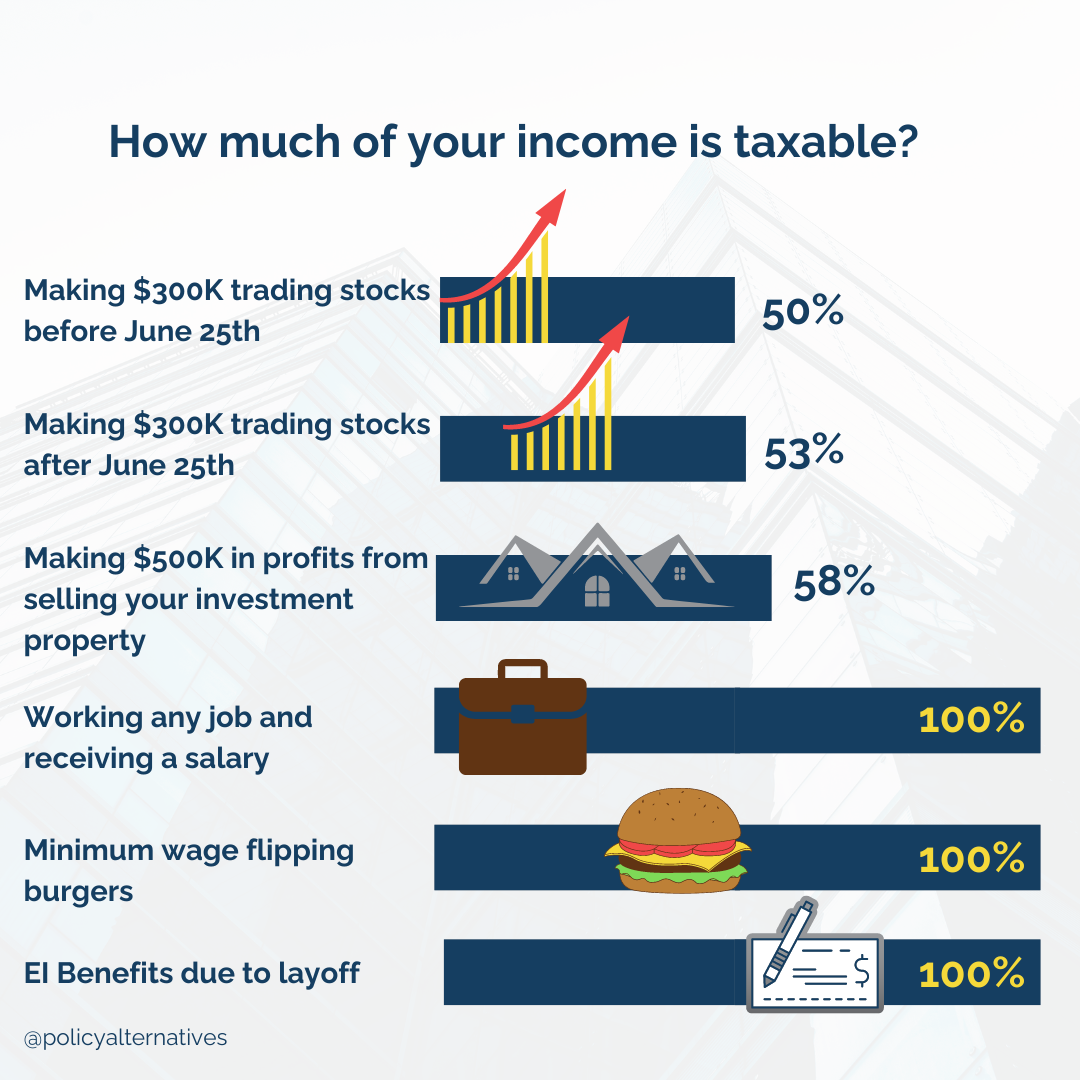

The inclusion rate is not the tax rate. The inclusion rate only determines how much of income gets counted as taxable by the tax system—that is, how much of it is even subject to taxation at all. Any other type of income—not made from buying and selling assets—is 100 per cent taxable. The inclusion rate for workers’ income is 100 per cent, not 50 per cent or 66.6 per cent.

Let’s consider some examples:

- If you’re a teenager working part-time at minimum wage to save for university, 100 per cent of your wages are taxable.

- If you’re a single mother making minimum wage at the mall working full time, 100 per cent of your wages are taxable.

- If you lose your job and have to rely on employment insurance benefits, 100 per cent of your benefits are taxable.

- If you lost your job as a server during the pandemic and had to rely on CERB, 100 per cent of your support was taxable.

- If you work at any job and make any amount of wage income, 100 per cent is taxable.

Capital gains, for some reason, gets special treatment. Prior to 1972, zero per cent of the income called capital gains were taxable, compared to 100 per cent of workers’ income, which were. This is why the Carter Commission on Taxation, which was convened in 1962 to study ways to make the tax system more fair, famously argued that “a buck is a buck”—that income from buying and selling things should be 100 per cent taxable, just like working income. However, in 1972 the Trudeau government settled on only 50 per cent of that income being taxable.

When it comes to this most recent change, the high dollar limit makes it so that only the richest will be affected. The vast majority of Canadians are not making over $250,000 per year in capital gains alone. In fact, only 0.13 per cent of Canadians are. Most Canadians make capital gains below $250,000 in a year and/or capital gains at that level would be generated by the sale of their principal residence, which isn’t taxed at all.

The inclusion rate also doesn’t abruptly jump from 50 per cent to 66.6 per cent if you made $249,999 versus $250,000. The new rate only applies to each additional dollar over $250,000 in gains —is at the 66.6 per cent rate and so the average inclusion inclusion rate goes up relatively slowly from 50 per cent to 66.6 per cent as gains climb further and further above the $250,000 threshold.

For example, if the capital gain was $300,000, the inclusion rate would be 52.7 per cent. The first $250,000 would have a 50 per cent inclusion rate and the extra $50,000 above the threshold would have a 66.6 per cent inclusion rate. So, all told, the average for the entire $300,000 is an inclusion rate of 52.7 per cent.

So, if you sold a stock and made a $300,000 profit before June 25, only 50 per cent of that is taxable. But if you sold a stock and made a $300,000 profit after June 25, when the rules change, 52.7 per cent of that is taxable. If you made a wild profit of $500,000 by selling your investment condo (again, that’s just the profit on the increased value) on June 26 due to the totally unaffordable real estate market, only 58.3 per cent of that is taxable. If you’re a rich executive who was paid $200,000 in stock options instead of money, only 50 per cent of that is taxable.

But if you’re a worker, no matter how much you make, 100 per cent of your income is taxable.

With this most recent increase to the inclusion rate, people making capital gains income are being taxed slightly more—just like those who just work for a living. They are still getting a great deal—nowhere near 100 per cent of their income is being taxed, even after the change. But we are getting ever so slightly closer to treating the rich like average workers when it comes to taxation. This is a step towards a more equitable tax system and reveals the privilege we continue to afford the richest and their income types, even after June 25.