For six weeks in May and June 1919, approximately 35,000 workers in the Prairie city of Winnipeg walked off the job to voice their frustration with a range of issues, from a lack of collective bargaining rights and union recognition to increasing inequality. Indeed, the strike was part of a broader wave of worker revolts that swept across Canada and the world in 1919, as working people in numerous Canadian cities and countries used the strike—the withdrawal of labour power—to push for change.

Though bosses and government officials ultimately crushed the Winnipeg General Strike, it remains one of the largest and longest strikes in Canadian history and an impressive display of the power of the strike as a tool of working-class protest. For as long as people have worked for others, walking off the job—going on strike—has been one of the most effective and direct methods of winning better wages and working conditions, among other demands. Because employers and governments rely on workers to produce goods and services, when workers refuse to work employers and governments are pressured to address workers’ grievances. This is why members of the radical labour union the Industrial Workers of the World often say “Direct Action Gets Satisfaction,” or “Direct Action Gets the Goods!”

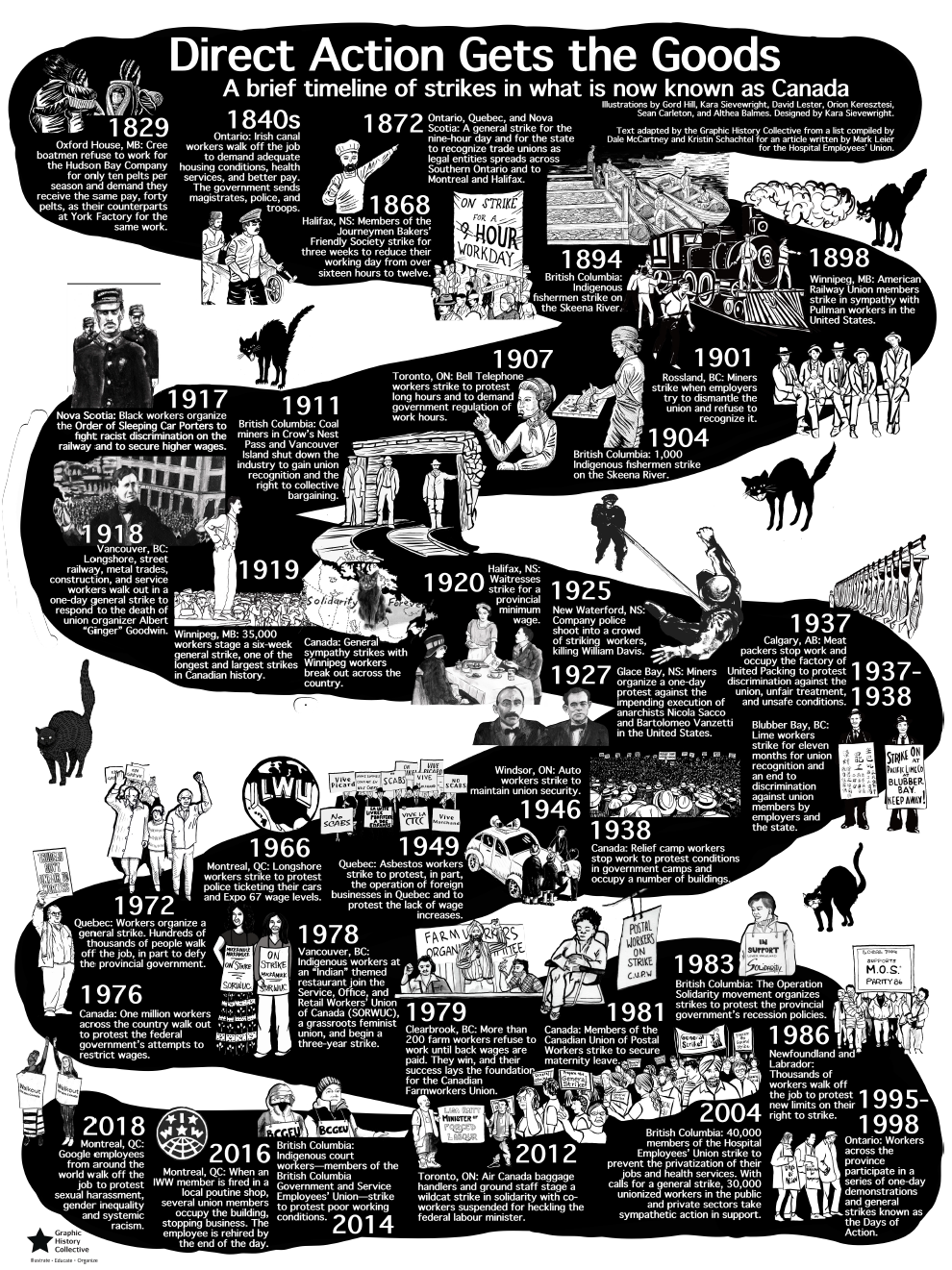

In recent years, we have come to view the strike narrowly, as a tool of last resort for unionized workers engaged in collective bargaining. But a closer look at the history of the strike shows us that for over 200 years, diverse workers in what is currently Canada have used the strike to fight for a better world.

In 1829, Cree boatmen in Oxford House, Manitoba refused to work for the Hudson Bay Company for only 10 pelts per season and demanded that they receive the same pay, 40 pelts, as their counterparts at York Factory for the same work. In the 1840s, Irish canal workers in Ontario walked off the job for adequate housing, health services, and better pay. In 1872, a general strike for the nine-hour day and trade union recognition spread across Southern Ontario and to Montreal and Halifax.

Workers continued to use strikes to address a range of issues throughout the 20th century. In 1902, members of the International Jewelry Workers’ Union in Toronto struck for two-and-a-half months after their union officers were fired. Meanwhile in Winnipeg, bakers at Paulin Chambers walked off the job to protest the company’s refusal to recognize female workers as members of the union. In 1914, the Trades and Labour Council of Canada regularly passed resolutions for a general strike to pressure the federal government to oppose World War I. In 1938, in the midst of the Great Depression, relief camp workers stopped work to protest conditions in government camps.

The number of strikes increased dramatically during World War II, and workers continued to use strikes as a tool of protest in the post-war period, too. In 1957, more than 65,000 railway workers walked off the job to support CP Rail firefighters who were to be phased out due to technological change. In 1972, the Common Front (a group of unions bargaining together) staged a one-day general strike in Quebec as part of their dispute with the provincial government. That same year, miners in Ontario struck to protest unsafe working conditions and lax regulation of worker health and safety.

Since the 1970s, the number of strikes has decreased, but workers still use the strike to push for change. In 1981, postal workers struck for maternity leave. In 1987, the labour council in Elliot Lake, Ontario threatened a general strike if an anesthetist was not brought to the town. In the mid-1990s, workers across Ontario participated in a series of one-day demonstrations and general strikes known as the Days of Action to protest the austerity policies of the provincial government. In 2008, 2015 and 2018 graduate student workers and contract faculty employed by York University struck for better wages and working conditions.

Workers can make great gains by withdrawing their labour power. But they also risk a lot. The stakes in class struggle are high. History shows us that employers and government officials will not hesitate to use all of the tools at their disposal to end strikes, including violence. To be successful, then, working people need to have a clear understanding of how strikes work, how workers in the past have used the strike successfully as a tool of protest, and how solidarity—rather than division, infighting or indifference—is the key to building a better world. In these tough times, we need to remember: direct action gets the goods!

The Graphic History Collective is a group of artists, researchers and writers interested in comics, history and social justice. Their comics show that you don’t need a cape and a pair of tights to change the world. In January 2019, the collective released Direct Action Gets the Goods: A Graphic History of the Strike in Canada and 1919: A Graphic History of the Winnipeg General Strike, both published by Between the Lines.