Lots of insecure jobs created in 2006, but more good jobs lost

Pundits have acclaimed 2006 as a banner year for the Canadian labour market, highlighted by an unemployment rate finishing the year at 6.3%, the lowest official average annual unemployment rate in more than 30 years. Overall, the economy created jobs for an additional 345,000 workers, up 2.1% from 2005, with an estimated 80% of these workers gaining full-time employment.

Some 65% of these full-time employment gains went to women, lowering the unemployment rate of adult women aged 25 and over to its lowest level in 30 years. On a regional basis, employment growth in the Western parts of the country continued its surge, centred around the oil-rich regions, with Alberta leading all provinces on a percentage basis at 4.8% or 86,000 net new workers. In terms of employment numbers, however, it was Ontario leading the pack by adding over 95,000 net new workers.

It is far from clear, however, that 2006 was the banner year for labour markets and workers that many, such as the big banks, claim it was. Beyond the heady numbers, lurking within the dynamics of the economy, are some real issues for concern. For a start, Central Canada is in the midst of an economic slowdown that, according to the official numbers, started in 2002 and continues to ravage the manufacturing sectors of Ontario and Quebec. These all-important–and seemingly forgotten—high-quality, high-paying manufacturing jobs are being eradicated from the economic bases of Ontario and Quebec faster than you can say “Steve Harper.”

Net manufacturing job-losses over this period have reached alarming heights of over 200,000 compared to their peak in 2002. The trend is becoming so pronounced that leaders of many of the nation’s industrial unions are calling on governments at all levels to step up and take action. A similar situation has occurred in the United States, where some two million manufacturing jobs have been lost over the same period. The U.S. media are castigating the Bush regime over this gutting of the American manufacturing base, but here in Canada, with a similar proportional manufacturing job loss, we have our national statistical agency, Statistics Canada, joining the chorus of bankers and business think-tanks in praising the performance of our economy and labour markets.

While it may be true that the Canadian economy continues to crank out jobs, many of the nation’s economists seem to have overlooked a simple economic fact: the economy requires some form of primary wealth creation. We cannot all work in banks or at Wal-Mart stores; somebody actually has to produce something.

Manufacturing in Canada, as of the end of 2006, employed over 2.1 million workers, or slightly more than 12% of the workforce. As the economy’s linch-pin and creator of the best industrial jobs, the manufacturing sector is of fundamental importance to the health of the entire economy. No other sector drives–both directly and indirectly–the pistons of economic growth. Ontario and Quebec make up 46.7% and 27.2%, respectively, of manufacturing employment in Canada. As denoted in Chart 1, the area of concern is the downward sloping trend that started in mid-2002. It takes a lot of job loss and restructuring of production capacity to start and maintain such a trend, and it will take a major effort to reverse it.

Chart 1: Canadian Manufacturing Monthly Employment Index

It should be noted from the chart that, while the recent declines are quite devastating for the economy, the growth in manufacturing from the mid-1990s up to its peak in 2002 represented quite a dramatic climb out of the depths into which it was plunged by the recession of the early ‘90s. It was surprising, in fact, given the myth that has persisted since the early 1980s that manufacturing within developed nations is not a viable economic growth strategy. In 2002, manufacturing in Canada reached a height that saw it surpass the early 1970s–the “high point” of the mass production era–by more than 30% in total manufacturing employment.

Note also that, while the total percentage of manufacturing employment as compared with total employment has slowly fallen to hover at around 12%, manufacturing production has changed much over this period, and these changes have altered the sector’s real and perceived employment levels. Over the past 20 years, for example, manufacturing firms have been contracting out more and more of their services, from janitorial to engineering. Many of these services, however, continue to form part of the overall value-adding activity of the entire manufacturing process. Because of the accounting methods and codification of industry statistics, many of the workers in these contracted-out jobs are no longer included within the manufacturing industry classification. This has led to an undercounting of actual employment within this sector. Although it is next to impossible to estimate, it should be noted as significant and skews the analytical concept in determining the size and relevance of the manufacturing industry.

The extreme growth in the service sector is part and parcel of this process. It is beyond the scope of this report to probe further into the manufacturing debate, but the growth that was witnessed during this period should be taken as an example of how an apparently high-waged manufacturing sector clearly remains a quite effective force for growth within a developed country’s economy.

In short, manufacturing still matters. Those who continue to spread the myth that manufacturing in developed nations is in its twilight should pay heed to this significant growth period. Some commentators have recently argued that a new knowledge-based economy is set to replace manufacturing as the main economic engine. However, while the knowledge-based economy is certainly growing in both scale and importance, one is hard-pressed to find evidence that it has approached some critical mass where it can supplant manufacturing as the principal creator of growth and jobs. In practical terms, in fact, the knowledge economy to some extent relies upon a healthy growing manufacturing industry for its success. Manufacturing is still the king, and ignoring this reality, from a policy perspective, is an economic disaster waiting to happen. Policy-makers must be extremely sensitive to this reality and not get side-tracked by the grandiose predictions of computer enthusiasts.

So far, the manufacturing job losses and their inevitable effect on the rest of the labour market has been seemingly contained, but many economists are waiting for the other shoe to drop. As noted by the TD Bank, “Sooner or later the manufacturing decline has got to cross-infect the remainder of the job market.” Eventually the multiplier effect of these job losses in our primary wealth-creating sectors will work their way through the economies of the two largest labour markets in Canada. Without some decisive action to address the root cause of the problems, job losses in the remainder of the economy are imminent.

Ominous signs are already apparent. For the first time in many years, GDP growth, starting in late 2005, has trended towards flattening, yet employment has continued to rise at a fairly even and sustained basis. This is quite odd behavior for the GDP and employment rates. Typically, the two follow one another around the graph like bees to honey. It is the nature of their relationship. There are points of departure, but typically these are short-lived. Undoubtedly at the root of this anomaly is the rapid replacement of high-value-adding/high-paying jobs within the manufacturing sector by low-value-adding/low-paying jobs in other sectors.

In other words, we are going through an unprecedented sustained period of employment growth based upon “growthless jobs”–potentially some kind of extended national-level calm before the storm. It may turn out not to be a permanent fixture of our economic future but, if one were to travel around the Windsor area in southern Ontario, it would be hard to envision the storm getting much worse.

While the employment numbers continue to rise, the overall national payroll going to workers losing high-paying jobs and being forced to take lower-paying, lower-quality jobs will eventually start declining. This will have a dramatic effect on domestic purchasing power, which is what the big banks are betting on to keep the economy riding high as export-oriented growth cools off in the wake of a slowing American economy. As reflected in the statistics, the U.S. economy is hurtling rapidly towards the wall. Potentially, these recent jobless high-wage workers, along with many others who find themselves newly employed at the local big-box retailer or call centre, will be forced to incur larger consumer debts, which are already at record-setting levels. The big bankers may even be relying on this upsurge in debt to offset lower wages in helping shore up domestic purchasing power. We know that consumption will not be financed from savings, since savings rates are also at all-time lows. About the only thing left on the consumer balance sheet worth talking about is the rapidly appreciated value of the housing stock in Canada. But if the depreciating markets of home valuations in the U.S. spill over the border into Canada, we could be in for a shock.

* * *

The second issue for concern centres on the much-heralded job growth in the West. There is no denying the explosive boom in Alberta, but the oil-related job growth is intrinsically linked to the price of a barrel of oil. It is booming now, but, if history has anything to teach us, it could burst tomorrow. Far be it for somebody to unravel the Gordian knot that determines the price of oil, but there is a certain amount of risk attached to such job growth. In fact, the spike in the price of oil over the past 3-4 years is largely to blame for what is wrong in Eastern Canada.

The Canadian dollar is now perceived by many in the international financial community as an oil-based dollar, with further extensions into prices within the resource industries such as nickel, uranium, and other raw materials. The high dollar is undoubtedly partially to blame for the manufacturing meltdown that is occurring in the East. This has created a precarious environment in which our dollar is determined, producing a chaotic business climate that manufacturers must contend with on a day-to-day basis.

Some economists have concluded that Canada’s dollar has caught the “Dutch disease.” The kind of exchange fluctuations witnessed in the recent past would wreak havoc on any supposed rationally-based economy. In early 2002, the dollar was trading at a mere 60 cents U.S., and some 12 months later it appreciated up over 80 U.S. cents. But we should not be afraid of a high Canadian dollar. A gently appreciating dollar is a sign of strength in our economy relative to others, and is quite manageable in the medium to longer-run scenarios. It is a complex concoction of revenue streams, competitive pressures, social costs, taxation, and a whole pack of important constructs that traditionally set in motion the mechanics and functioning of exchange rates. Having it flip around like a fish out of water is about as productive as having Industry Canada, in a recent research paper—Policy Responses to the New Offshoring: Think Globally, Invest Locally–claiming that the troubles plaguing Canadian manufacturing companies are due to their not outsourcing enough!

Bolstered by growth in the West, the labour markets of the nation seem to be riding around two extremes: decline in the East, and growth in the West. But the degree of job creation in the West, while impressive and mainly masking the declines in the East, are no match for the mis-firing economic engines of Ontario and Quebec. Resource extraction industries have become quite capital-intensive and do not carry the kind of employment creation they once did. The entire extraction industry in Canada, as of December 2006, employed 342,000 workers, and there are signs that this sector may be starting to cool as oil prices begin to trend downwards.

This reduction in oil prices is a boon for manufacturers in the East, coming in the form of both a lower dollar and reduced energy prices. Both will be helpful, but the heart of the economic problems lies much deeper. A faltering American economy is starting to have its effect on our economy, with a special emphasis on the transformations in the automotive sector and the falling market shares of the Big Three auto makers, combined with a global decline in the auto sector in general.

* * *

Another generally overlooked aspect of the apparent success of the labour market in 2006 concerns the inequitable distribution of wealth. It is ironic that, amid the parade of shining labour market reports, Statistics Canada released a study entitled Revisiting Wealth Inequity, which concluded that the distribution of wealth within the country is at its most inequitable level in decades. The report noted that the Gini coefficient, a measure of wealth distribution, has risen from 0.691 in 1984 to an abysmal 0.746 in 2005. A standardized internationally recognized measure, the Gini coefficient equals zero when all families within a nation receive an equal share of wealth, and equals 1.0 when one family receives all the wealth. Perhaps more dramatic, the report shows an increasing trajectory of this important margin. If we further consider the fact that participation rates within the labour market are at all-time highs (outside of the war-time periods), we could assume that more people are working than ever, yet the rewards for working are being distributed more unfairly than ever, with disturbing and potentially disruptive social implications.

This increasingly dystopian polarization in wealth has various causes and dimensions, and we briefly examine two of them. The first is that compensation is being concentrated ever more massively at the upper end of the income scale, and the second is that a large and growing component of the workforce is comprised of precarious low-quality, low-paying jobs.

Pay levels for those in the upper echelons of the labour market are getting staggeringly out of touch with the pay levels of the average worker. As reported by the CCPA early in the New Year, the average annual pay of the 100 top CEOs in Canada in 2005 exceeded $9 million, compared to an average of around $38,000 for their employees. This means that the average high-paid CEO this year received as much remuneration by 10:04 a.m. on New Year’s Day as one of his employees will be paid for the entire year. No wonder that even the mainstream media are taking note of the disparity. Hardly a day goes by now without some headline relating to the enormous salaries, bonuses and perks enjoyed by corporate executives, or to the multi-million-dollar “severance” packets they receive when retiring or even being fired. These executive pay packets are becoming so exorbitant and common that in 2006 special statistics were being set up in the U.S. and Canada to measure the effect such huge payments were having on the GDP. They are certainly having a quite measurable impact on corporate bottom lines because, ultimately, it is the consumer who must pay for this greed through higher prices.

The enormous amounts handed out to CEOs come mainly from corporate profits and surpluses, and stand in sharp contrast to the anaemic shares of the profits now being re-invested in infrastructure, research and development, and other productive measures.

Closely linked with this inequity in wealth distribution is the segmentation of the labour market into two groupings: those with low-quality employment and those with high-quality employment. With low pay and benefits, low employer attachment, low labour standards, low unionization rates, and, most importantly, with governments at all levels permitting and even encouraging such regressive labour practices, precarious employment has become a fixture within our society.

Over the past several years we have seen participation rates within the labour market (on an annualized average basis) consistently reach and surpass the 67% mark–some of the highest rates ever recorded. This especially holds true for women, who have set all-time records, achieving a participation rate of 62.1% in 2006, the highest in more than 30 years. With these increased participation rates set against the backdrop of the worsening wealth inequity we are witnessing, one can intuitively deduce an increasing dimension of low-quality employment. Unfortunately, the statistical programs used to monitor the labour market in Canada do not easily lend themselves to investigate the degrees of job quality or precarious employment. The data, at best, are quite dated and typically consist of a collection of information from various surveys.

In one such report, in May 2005, from a series called Vulnerable Workers’ Series, the Canadian Policy Research Networks estimated that 16.3% of full-time workers earned less than $10/hr in 2000. The study focused on workers aged 15-64, who were not full-time students and worked mainly full-time. Some of the key findings of these low-paid workers found there is a strong gender dimension to low pay: about 22% of women were low paid in 2000, compared to only 12% of men. The report also found that the share of jobs paying less than $10 per hour (in real 2001 dollars) has not fallen since 1981. As indicated by the dates in the study, not much in the way of monitoring occurs in a timely or regular interval. There is much work to be completed in bringing to light the nature and dimension of precarious employment and its practices—practices that seem quite persistent, prevalent, and skewed towards women within the economy.

* * *

The fourth and final point that needs to be addressed is the current notion of “tightness” in the labour markets, perceived by the Bank of Canada as the biggest danger to our economy. Translating the Bank-speak, tight labour markets equals wages gains, which somehow equals the biggest danger to the economy. So how tight are labour markets, given the degree of fear-mongering coming from the Bank of Canada? Most mainstream economists maintain that there is some “natural” rate of unemployment in any given economy. When an economy starts displaying an unemployment rate close to this “natural” rate, pressure starts to build among employers who must contend with shortages of workers. The key question that we will focus on is what exactly is the natural rate of unemployment and exactly how is unemployment measured.

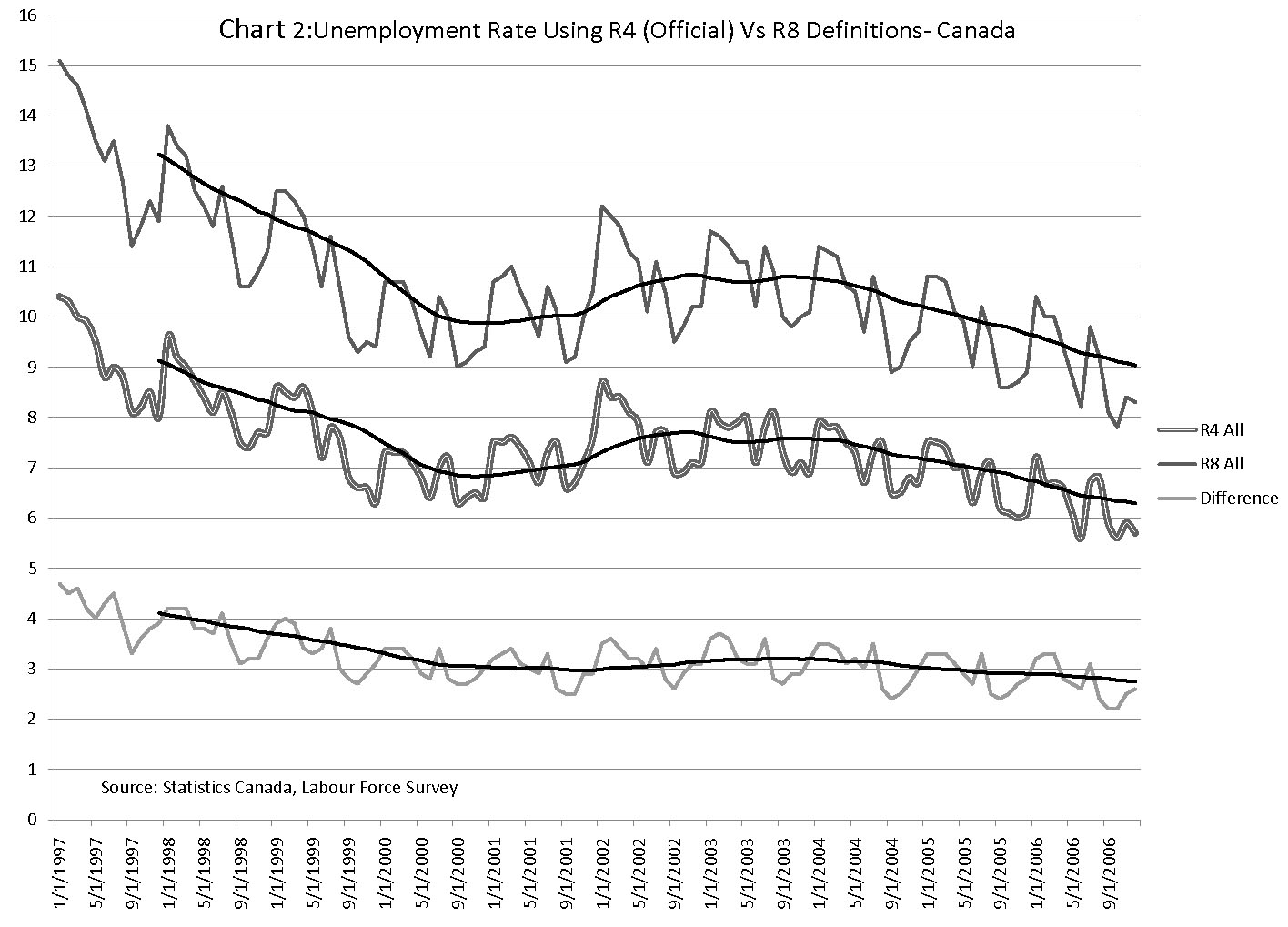

In Canada, StatsCan’s Labour Force Survey is used as the official vehicle for measuring unemployment. However, the actual unemployment rate derived from the labour force survey is not a measure of unemployment. If you examine the survey vehicle closely, you must conclude that it is a measure of the degree of job search efficiency among those in the country who are unemployed. The actual question used within the survey process only classifies a person as officially unemployed if he or she has indicated they have “looked for work within the last four weeks.” (Seems you can’t be asked a straight question even in your most desperate of times.) This is actually the implementation of the R-4 criteria of defining and measuring unemployment. The R series of definitions of unemployment is an internationally standardized rating system used by labour statisticians to classify the differences between national statistical agencies across the world in measuring the rate of unemployment within the labour market. It ranges from an R-1 to an R-8 rating. Canada implements the R-4 definition, which distinguishes itself from other classifications by specifying that the unemployed person must have been actively seeking work within the previous four weeks of the survey reference week. The U.S., on the other hand, makes use of the R-3 rating, which further stipulates certain measures that the respondent must have performed within the job search process to actually be counted as unemployed.

The whole process really seems to be an exercise in futility and loaded with political ramifications. The R-8 rating is most likely the best of the measures in defining unemployment with the objective of determining the extent of tightness in the labour supply. It does so by including “discouraged” workers within the ranks of the unemployed: those who have given up looking for work within the last four weeks of the survey period but are still willing and able to work; and it also includes some components of under-employment within an economy, by including a proportion of those working part-time but wanting full-time work.

Statistics Canada actually performs the calculations for all the various R ratings and publishes them on its CANSIM data series. So, upon examining Statistics Canada’s estimates of unemployment using the R-8 rating in defining unemployment, we get a national annual unemployment rate in Canada of 9.0% rather than the 6.3% under the R-4 definition. That represents approximately another 400,000 Canadians added to the ranks of the unemployed, over and above the official 1.1 million or more workers deemed officially unemployed using the R-4 definition. Having the Bank of Canada continually warn of the dangers of a tight labour supply using the official rate of unemployment of over 1.1 million workers is a stretch, but, given the R-8 definition and the more than 1.5 millions workers in the economy defined as unemployed, any talk of tight labour supplies is pure nonsense. It is irresponsible for a national institution with so much power and responsibility for the effective functioning of the economy to engage in such baseless fear-mongering.

Chart 2: Unemployment Rate using R4 (Official) vs R8 Definitions – Canada

* * *

It is quite a dubious exercise in self-congratulation that our government leaders take when they hold up the latest glowing labour market reports and join with the banks, the business community, and corporate think-tanks in patting themselves on the back for a job well done. Completely overlooked is all the pain and deprivation of wealth inequity, labour market polarization, and the wrenching job-losses and minimum-wage employment that afflict the working poor. Ignored, too, is the anguish of the thousands of Canadians displaced from secure and well-paid jobs and forced to take low-paying part-time work.

As for Statistics Canada, it is irresponsible and deceptive of a national statistical agency to allow such incomplete data and information about employment and the labour market to be taken out of context and misused by politicians and business leaders to proclaim that things are just fine with the economy and with employment.

Within the currents and eddies of a continually expanding globalized economy, it is the streams of wealth and how they are distributed within a national setting that determine the overall success of an nation. Simply creating jobs is no longer the bellwether measure of an economy’s health. It is the number of quality jobs that is important, and their maximization ought to be a top economic priority for our leaders. Without an accurate measuring stick, however, such an objective can be kept low on the political and business agendas without incurring much public disfavour. In fact, it is one of the most disturbing trends in the labour market during 2006 that underline this point.