The white nationalist rallies that have peppered the country, beginning in the early part of 2017, are tangible indicators that there is a viable and increasingly active right-wing extremist (RWE) movement in Canada.

In 2015, Ryan Scrivens and I published the first contemporary—and comprehensive—assessment of Canadian RWE activity. We estimated, conservatively, that just over 100 groups were operating across the country. However, in the lead-up and aftermath of Trump’s upset presidential victory in the U.S., the RWE movement appears to have shifted quantitatively and qualitatively. Many groups are larger, bolder in their online and offline activism, and there are more of them (up to 25% more). There is also evidence that, with the emergence of the alt-right, the audience and membership associated with the contemporary RWE movement in Canada is broadening.

When we think of the extreme right, we typically envisage the tattooed, snarling, angry young white male. There is a great deal of truth to that image. Members of La Meute, Atalante, and Blood and Honour do not make any effort to soften their malevolent image. Selfies and other photos posted to RWE websites often feature images that reflect “tough guy” postures. Yet these are the storm troops, the front lines. Behind the lines stand others who seek to further RWE causes through slightly more subtle means, in a way that makes it more palatable, more acceptable to a public sensitized by a generation of discourse of equality, multiculturalism and diversity. In a word, hate is increasingly “mainstream,” and thus increasingly legitimate.

The alt-right, which styles itself as the “intelligentsia” of the right, can take a lot of credit for this mainstreaming of hate. In truth, there is little to distinguish them from the traditional far-right. The messaging is the same—the West is losing its distinct Euro-culture thanks to a misguided emphasis on multiculturalism and open immigration—while the framing may vary, to make it more palatable, as noted. Rather than use the coarse language of race and racism, the alt-right speaks of culture loss, or preservation of “Canadian values.” It’s much harder to find fault with this coded language in isolation. It is the cumulative effect of their strident critiques of the Liberal Party (Trudeau in particular), of diversity policy, of globalization, as examples, that reveals the exclusionary core of their ideology.

Like contemporary right-wing populists, such as Donald Trump and Doug Ford, the alt-right has a certain appeal for that portion of the population that eschews both the principles and practices of multiculturalism, which they feel threaten the state of their lives or of the nation (and usually both). Public opinion polling over the past couple of decades reveals antipathy if not downright hostility among these people toward some of the same issues targeted by the alt-right and the far-right. The message of hate disseminated by RWE groups speaks to existing popular concerns: this is at the heart of the legitimacy of their rhetoric.

For example, a Maclean’s poll released in 2013, during the course of my project with Ryan, found that 54% of Canadians held an unfavourable view of Islam, up sharply from 46% in 2009. To put this in perspective, 39% held an unfavourable opinion of Sikhism, while all other religions were regarded unfavourably by less than 30% of Canadians. The sentiment reached its highest rating in Quebec, a province with extensive skinhead activity in particular among other RWE groups. A 2015 EKOS poll revealed that opposition to immigration had doubled since 2005, to 46%. In the same poll, 41% of respondents indicated they felt there were “too many” visible minorities immigrating to Canada.

***

How are these concerns leveraged to draw people into the RWE movement? There is a continuing reliance on street-level and face-to-face recruitment. Recent months have seen a resurgence of old-fashioned strategies of pamphleting, whereby flyers are distributed locally on utility poles and windshields, even in mailboxes.

On November 14, 2016, for example, Toronto residents woke up to find racist posters scattered across city neighborhoods. The hateful propaganda, titled “Hey, white person,” encouraged readers to join the alt-right movement and subscribe to a list of “pro-European” websites. That same morning, residents in a predominantly Chinese community in Richmond, British Columbia, were shocked to find racist pamphlets in their mailboxes. The flyers stated: “STEP ASIDE, WHITEY! THE CHINESE ARE TAKING OVER.” While crude and typically not very creative, such pamphlets have the capacity to draw particularly disaffected people to related websites where the messaging is more expansive.

Many individuals are lured in by people they know personally. Group members are often friends or associates, sometimes even relatives of potential recruits, prior to joining. They are thus encouraged by people they know and presumably trust. Others may be new “acquaintances,” people met in bars and clubs with whom adherents and promoters strike up conversations. They strive to find mutual points of interest and, often, grievance. Just lost your job, you say? Women aren’t interested in you? Here are some explanations for your woes!

So begins the process of pulling people into the movement. The next step may simply be another beer and more conversation. This may be followed by an invitation to visit a particular website, and later, the closed forum associated with a group. Or the potential recruit might be introduced to white power music, seductive in its beat and messaging. In any event, the process is generally gradual and seemingly sporadic.

There can be no doubt that the internet has facilitated recruitment to the RWE movement. It is an add-on to personal recruitment as well as a standalone tool for “self-radicalization” of lone actors. Whether directed there by recruiters or pamphlets, or discovered independently by seekers, the various websites, social media platforms and discussion forums have the potential to engage the imagination of would-be right-wing extremists.

There is something for everyone. Video games will appeal to youth, as do the frenetic white power music and related music videos. Dating sites will appeal to others. International forums allow connections with like-minded peers elsewhere across the globe. Indeed, sociability is particularly important in so much as users of these online websites, chat groups and social media platforms find themselves able to freely communicate racist or sexist or other sorts of views that might be unpalatable in other contexts. At the core of all of these mechanisms, however, is consistent messaging about the inherent superiority of those of white European heritage relative to all other identity groups.

The current vibrancy of the RWE movement in Canada is cause for concern. Even CSIS (the Canadian Security Intelligence Service) was finally forced to acknowledge that right-wing extremism represents a “growing threat,” something they had heretofore ignored.

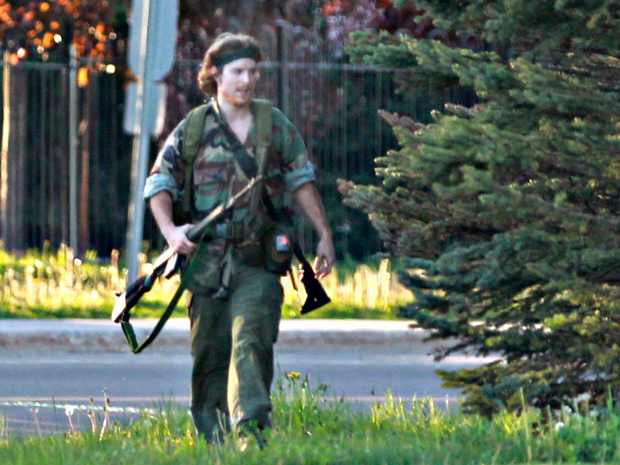

Far-right ideologies have inspired 19 murders in the past four years. In 2014, Justin Bourque (pictured) killed three RCMP officers in Moncton. In 2017, Alexandre Bissonnette murdered six Muslim men in Quebec City. And in 2018, Alek Minassian killed 10 pedestrians on a Toronto sidewalk. All of these acts were inspired by some strain of RWE, whether anti-statism, Islamophobia or misogyny. These acts of terror alone should inspire recognition of and action against the far-right.

We have seen some encouraging grassroots activism in the form of anti-racist rallies countering the racist rallies. And we have seen some symbolic gestures at the federal level, in the form of Motion 103 condemning Islamophobia and other forms of systemic racism. Yet we have seen far too little in the way of concentrated state-sponsored counterterrorism efforts directed toward the far-right. If the hatred and violence is to be eradicated, it will require a much more systematic strategy of engagement and containment. There is work to be done.

Barbara Perry is a professor in the faculty of social science and humanities at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology (UOIT), and one of the world’s foremost authorities and renowned authors on hate crime. She is Director of the newly formed Centre on Hate, Bias and Extremism at UOIT.