How reforms to tax policy could help close the wealth gap in Canada

A 2014 report from the CCPA called Outrageous Fortune documented the increasing wealth gap in Canada. Using data from Statistics Canada, CCPA economist David Macdonald demonstrated that for every new dollar of real wealth generated in the country since 1999, 66 cents has gone to the wealthiest 20% of families. As a result, in 2012 Canada’s wealthiest 86 families had a combined net worth of $178 billion, roughly the same amount of wealth held by the country’s poorest 11.4 million people.

“[M]any gasp at the fact that Canada’s richest 20% of families take almost 50% of all income,” wrote Macdonald. His comments were more than a rhetorical device: people do want change. Another report in 2014, this one from the Broadbent Institute and based on the same data, surveyed Canadians on their views about the country’s wealth gap. It found that “the desire for a more equitable distribution of wealth holds regardless of demographics or past political preferences, including those who voted for the Conservative party in 2011.”

Clearly there is an appetite among voters to do something about economic inequality. But do what? I argue that Canada’s tax system contributes to and exacerbates this type of economic inequality in Canada, and that a few possible changes to that system would have an immediate positive effect. Some of these changes would affect or eliminate tax breaks that may appear, at first, to be broadly beneficial for a very limited group of taxpayers. But if we are honest about who really benefits most from these measures, and their costs, I think people will agree they are overdue for reform.

***

We tend to think of taxes and the tax system as being primarily geared toward revenue generation. That is, taxes are collected from individuals and corporations then spent on government programs. In fact, our tax system is meant to serve many different purposes, including redistributing income and wealth in an effort to reduce inequalities between rich and poor. For example, progressive marginal income tax rates—rates that go up at intervals depending on how much you earn—are used to ensure there is a more equitable distribution of disposable income than there would be if everyone, regardless of pay, were taxed at the same rate.

But when it comes to wealth redistribution (the distribution of financial, property and other assets) the tax system fails completely and indeed exacerbates the wealth gap. The main reason is that Canada has an extremely low overall tax rate on capital (wealth). Until this issue is redressed, the gap between the rich and poor in Canada will continue to grow.

An international comparison demonstrates this point. OECD statistics show that Canada lags far behind both the United States and the United Kingdom with respect to the overall rate of taxation on capital. For example, Canada is one of only seven of the OECD’s 34 member countries that does not have some form of estate or gift tax, the most commonly used tool for taxing capital.

Combined with Canada’s non-taxation of capital gains arising from the disposition of property (bonds, shares, real estate and other valuables), the absence of an estate or gift tax results in huge pools of wealth being passed on, tax-free, from generation to generation. This oversight is not just expensive for the government, but it tends to widen the gap between rich and poor in Canada.

***

Subject to certain exceptions, which I’ll address in a moment, if a taxpayer makes money disposing of a capital property, that profit (the difference between what it cost when you acquired the property and what you eventually sold it for) is considered a capital gain, only half of which is taxable under Canadian tax rules. (In the past, three-quarters of the capital gain was taxed, decreasing to two-thirds and finally to half in the year 2000.)

To see how this is preferential treatment, consider that there is no way to avoid paying taxes on 100% of your income. In other words, when wealth creates wealth it is taxed more generously than most people’s main source of income, their labour.

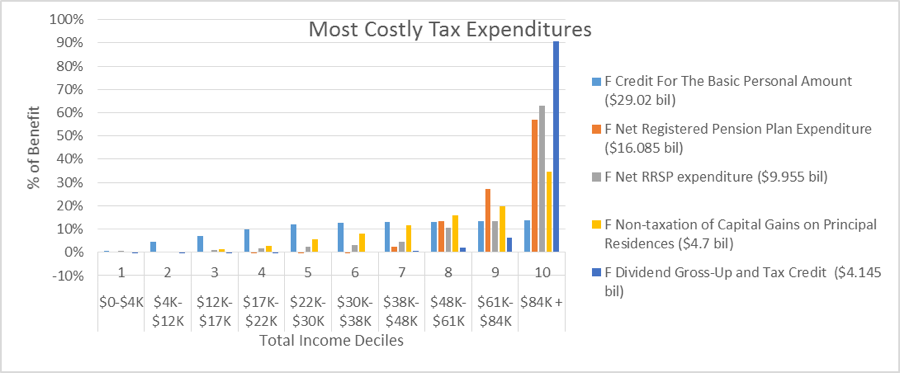

Each year, the federal government publishes an account of tax expenditures that details the value of tax revenues foregone because of tax breaks on things like capital gains. It is a lot of money. In 2016, the cost to government of taxing only 50% of capital gains is estimated to be over $6.3 billion. Contrast that amount with the modest $210 million in taxes not collected on social assistance payments.

While some capital gains are taxable, if only in part, many others are not taxed at all. A well-known example is the tax exemption for gains made selling a principal residence (your home). The policy of not taxing home sale profits is clearly meant to encourage home ownership. It is a popular exemption that can be extremely valuable to people of varying incomes, especially when the real estate market is hot. It is therefore difficult to imagine any government willing to end this tax break.

Source: Out of the Shadows: Shining a light on Canada’s unequal distribution of federal tax expenditures, by David Macdonald (CCPA, 2016).

But taken together with the other exemptions for capital gains, there is a problem here in the form of a large and substantially inequitable tax advantage going to those with the money to invest in a home. The comparison with income tax is useful again here. Tax-free profit on property is not usually due to any particular effort on the part of the taxpayer, especially in metropolitan areas such as Vancouver and Toronto, whereas a person’s labour is fully included in their taxable income.

Consider also that the higher the profits are from home sales and the hotter the market, the more unlikely it is that lower-income earners will be able to buy in and one day realize the same gains. While many homeowners like the capital gains exemption on principal residence sales, it is worth discussing a cap on the tax expenditure. For example, would it not be reasonable to tax windfall profits (above $500,000) on more expensive homes? This would serve a dual purpose of cooling over-hot real estate markets while letting low- and middle-income homeowners keep the tax benefit.

***

Another significant exemption from taxation relates to gains arising from the transfer of capital property to a spouse. This tax loophole allows one spouse (a person who is married or who is in a common-law relationship lasting at least a year) to defer taxes on the transfer of capital property to the other during their lifetime and, importantly, also on death. Taxes must eventually be paid when the spouse who receives the property disposes of it or dies, but overall the policy encourages people to keep wealth in the family, as a disposition to anyone else would trigger an immediate tax liability.

The issue of preferential tax treatment of spouses is complex: the idea that one should be able to move property within a relationship without having to pay tax has its obvious attractions and rationale. But it is important to note the class dimensions of this feature of the Canadian tax system.

Many people believe it is to their advantage to be taxed as a couple, and that they will pay less tax than they would if taxed as two individuals. That assumption is correct in some cases, mostly affecting those in middle to upper income brackets, and mainly due to the intra-spousal tax-free transfer of capital. But couples with low incomes and little or no wealth cannot benefit from this tax break. Furthermore, these couples often pay more tax when taxed as a couple than they would when taxed as individuals.

One reason for this is because individuals can lose the GST tax credit and, if they have children, some portion of the Canada Child Benefit when they are taxed as a spousal unit. Those tax breaks come with an income ceiling, based on aggregated spousal incomes, above which one can lose the benefit. This issue was illustrated starkly when lesbians and gay men were included as spouses for tax purposes. The result was a tax windfall for the government because couples with low incomes were now paying more tax than when they were taxed as individuals.

If we are serious about redistributing wealth in Canada and removing the current tax penalty for couples with low incomes and little wealth, removing the tax exemption for intra-spousal transfers of capital property is a good place place to start.

***

Some dispositions of capital property take place on a completely tax-free basis. One of the most expensive tax loopholes in this category—the lifetime capital gains exemption—will cost the federal government an estimated $1.5 billion in 2016. The tax exemption covers profits from disposing of shares in a small business corporation or certain farming and fishing property.

While the capital gains exemption is meant to encourage entrepreneurship, it is but one of several big bonuses linked to activities that already benefit from significant income tax–related breaks. Those who earn business income enjoy many more tax breaks than those who receive employment income, and several tax breaks are already designed specifically to reduce the tax paid by farmers and fishers.

If we focus on the fairness of Canada’s tax regime, and how effectively it helps redistribute national wealth from top earners to those making lower incomes, we cannot forget tax shelters such as registered retirement savings plans (RRSPs), registered education savings plans (RESPs) and tax-free savings accounts (TFSAs). Taxes are deferred on RRSPs until they are removed from the plan in retirement, while capital gains in RESPs and TFSAs escape taxation entirely.

There are tax policy reasons for encouraging people to contribute to these plans. For example, a well-financed RESP can make paying for a child’s post-secondary education easy. But we must ask ourselves who is taking advantage of these tax shelters and, more importantly, who has no access to them because of their low income and lack of wealth.

Contributing to RRSPs, TFSAs and RESPs is dependent on having the discretionary income available. Studies show, for example, that men contribute more than women to these savings vehicles, and those with high incomes save more than those with low incomes. The Parliamentary Budget Officer has reported on how, over time, foregone government revenues from TFSAs will represent a staggering pool of untaxable accumulated wealth—a process that in itself perpetuates inequality in Canada while impoverishing efforts at redistribution.

As mentioned already, Canada is further limited in this respect by being one of the few countries that does not levy an estate tax, succession duties (tax on inheritances) or gift tax. The federal government ceded this field of taxation to the provinces in 1971, but eventually they dropped out, too. In 1993, the Ontario Fair Tax Commission called on the federal government to introduce an estate tax, as exists in so many of Canada’s OECD contemporaries, but there have been no serious moves in that direction since then.

***

As long as Canadian tax breaks for capital gains remain as they are, the wealth gap will continue to grow. While our income tax system is relatively progressive in the way it helps redistribute the national income, we need to get serious about the redistribution of wealth in Canada. Our record is woeful compared to other countries. It is time to start removing some of our tax exemptions on capital property, and to consider the use of an estate and gift tax regime as part of any effort to redress economic inequality.

Claire Young is Professor Emerita at the Peter A. Allard School of Law at the University of British Columbia, where she taught for many years. Her area of specialization is tax law and policy and she is the author of several books and articles on the topic, including “Women, Tax and Social Programs: The Gendered Impact of Funding Social Programs Through the Tax System,” and “What’s Sex Got To Do With It?” Tax and the ‘Family.’”

This article was published in the January/February 2017 issue of The Monitor. Click here for more or to download the whole issue.