Wealth taxation is back on the progressive political agenda. It is both a refreshing new idea and a return to vogue of a policy established decade ago in Europe. Some remember it as part of François Mitterrand’s 110 propositions pour France, a joint electoral platform in 1981 with the Communist Party that carried him into the Élysée Palace. The solidarity tax on wealth survived multiple right-wing presidents, only to fall recently to President Macron.

Even so, it is an idea whose time has come in North America. It continues to exist in three OECD countries, and both Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, two of the leading three Democratic contenders for U.S. president, have a plan to tax wealth in their platforms. The NDP also included a proposal for a wealth tax in its 2019 election platform, which was met with backlash and bad-faith critiques from the usual suspects.

Matthew Lau, who has written for the right-wing Fraser Institute and Atlantic Institute for Market Studies, called it “class warfare” and “confiscatory” in a Financial Post column. This was followed by another piece in the same publication by the Montreal Economic Institute’s Gael Campman, who claimed taxing wealth would be a “tragic mistake,” seemingly oblivious to the existence of property taxes in Canada. Calling it a “demagogic ploy that ends up being counterproductive,” Campman brings up the prospect of the widely discredited “Laffer effect” of falling tax revenues from increasing taxation.

In a slightly more serious challenge, Robin Broadway and Pierre Pestieau call the wealth tax “Over the Top” in their recent C.D. Howe paper of the same name, stating that it isn’t needed, and it would be more efficient to raise taxes on capital gains. Why not do both? Recent studies such as the CCPA’s Born to Win have shown that Canada’s wealthiest 87 families now own the same amount as the lowest-earning 12 million Canadians, which is approximately equivalent to what everyone in Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick collectively owns. In Canada, just two billionaires (David Thompson and Galen Weston) own as much wealth as a third of Canadians.

A bold tax policy package is sorely needed to address this kind of wealth hoarding, which contributes to soaring inequality. Along with a host of other progressive measures, the wealth tax in particular sits in the enviable position of being at the nexus of both good policy and good politics.

According to a recent Ipsos poll, 67% of Canadians believe that “Canada’s economy is rigged to advantage the rich and powerful.” Another poll conducted by Abacus Data found that 67% of Canadians also support the idea of a wealth tax, including 58% of Canadians self-identifying as “right-wing” and 64% of those who say they are in the political “centre.”

***

In his critique of the NDP’s modest wealth tax proposal, Campman alleges it would force poor farmers to sell their land and cause capital flight. Lau asks how the tax could work when wealth in financial assets can vary day by day depending on the stock market. As the OECD has pointed out, there are ways of getting around all these problems.

The best wealth tax systems have a series of exemptions regarding most forms of middle class wealth, such as pensions and primary homes, as well as exemptions for agricultural property. Assessments can occur every 3–5 years with options to apply for reassessment if a significant change in value occurs, and payments can be made in instalments for those taxpayers facing liquidity constraints.

Wealth taxes can apply to both domestic and international assets, be tied to citizenship and be negotiated by international tax treaties—to eliminate the incentive for capital flight. As proposed by Elizabeth Warren, you can introduce an “exit tax” at the same rate as an estate tax to seize assets from those who do choose to renounce their citizenship. With a rigorous enforcement regime, along with legislation to tackle tax havens, taxing wealth isn’t a pie-in-the-sky or unrealistic idea. It just takes political commitment and good policy design.

Casting aside the nitty gritty, the fundamental question we really should be asking ourselves when we design our wealth tax is should we allow billionaires to continue to exist?

Gabriel Zucman and Emmanuel Saez, two economists at the University of California, Berkeley who advised Elizabeth Warren on her wealth tax proposal, write that the “revenue maximizing rate” runs as high as 6.5%—far beyond the NDP proposal of 1%. According to the economists, such a low rate would provide permanent revenues due to its quite limited effect on wealth concentration. Higher rates of wealth taxation, say, up to 10%, would more effectively dismantle entrenched wealth concentration over time with the trade-off being the loss of a permanent and reliable source of tax revenue.

Bernie Sanders’s recently unveiled wealth tax plan would cut in half the wealth of the typical billionaire over 15 years, according to Saez and Zucman. When the New York Times interviewed Sanders about his plan, they asked if he thought billionaires should exist in the United States. “I hope the day comes when they don’t,” he responded, adding, “It’s not going to be tomorrow.”

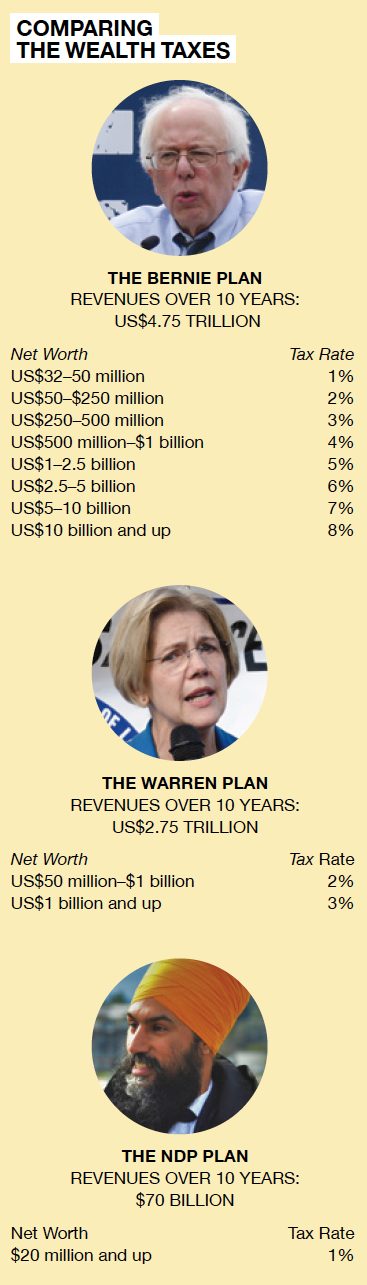

Sanders’s wealth tax (see box) is much more aggressive and much more steeply progressive than Warren’s plan, which begins at a 2% tax on wealth above US$50 million and adds an additional 1% surtax above the billion-dollar mark. The revenue differences are large: over 10 years, Warren’s plan would raise US$2.75 trillion while Sanders’s would raise US$4.35 trillion. The other significant difference is how the Sanders plan obliterates wealth concentration while Warren’s plan has a much more limited effect due to the fact that the wealth of the richest Americans grows at an average rate of 6.6% a year.

By comparison, the NDP’s plan for a 1% flat tax rate on wealth above $20 million seems quite modest. The Parliamentary Budget Officer estimates the NDP proposal would rake in approximately $70 billion over 10 years, a value that includes the assumption that revenues from the wealth tax will be reduced by about 35% due to tax avoidance.

Rather than being “confiscatory,” as Lau suggests, Saez and Zucman write that “the marginal utility of a billionaire’s wealth is close to zero” and therefore “the revenue consequences of taxing billionaires outweigh the welfare consequences on billionaires.” Imagine for a moment what we could do if Canada plowed $70 billion into reducing poverty, fighting climate change or tackling the housing crisis. Canada’s oil barons can manage with one less yacht.

***

We can see that a wealth tax would be good for redistribution. What of wealth concentration? Should we not also tax inheritances in order to stop the out-of-all-proportion pooling of family wealth through massive intergenerational transfers? The issue here is political. Sometimes inheritance taxes poll poorly, even when the tax only targets the passing down of unearned wealth. Even so, should we continue to allow oligarchs to control so much wealth and power while other Canadians continue to live in poverty?

The proper design of any wealth tax system ought to both balance revenue generation and target wealth concentration. Which is why if we swear off an inheritance tax, we should be jacking up wealth tax rates. And if we shy away from steeply progressive wealth tax rates, we need to at least implement an inheritance tax.

French economist Thomas Piketty, best known for his best-selling book Capital in the 21st Century, has just put out a new book entitled Capital and Ideology. In it he proposes a wealth tax with a rate that goes as high as 90% for those worth over two billion euros (almost $3 billion). He also states that billionaires actually harm economic growth and should be completely taxed out of existence. In a world in the midst of a climate emergency, it may also simply be necessary.

Piketty writes in Le Monde that “it is increasingly clear that the resolution of the climate challenge will not be possible without a strong movement in the direction of the compression of social inequalities at all levels.” This is because, “at world level, the richest 10% are responsible for almost half the emissions and the top 1% alone emit more carbon than the poorest half of the planet. A drastic reduction in purchasing power of the richest would therefore in itself have a substantial impact on the reduction of emissions at global level.”

When designing our wealth taxes, we should perhaps consider not only their redistributive power but also how they can attack the entrenched power of economic elites—and how this might help us save the planet along the way. As Piketty suggests, a wealth tax could be instrumental in shifting carbon intensive and socially useless elite consumption patterns.

Looking forward into the next decade, when large-scale economic decarbonization is on the agenda, we should also ask ourselves if this should mean moving toward a billionaire-free world. In the future we want to build, if we are asked the question, “Should billionaires exist?”, we should be able to confidently and resolutely answer: no.

Nate Wallace is Policy Director of the Young New Democrats.