When we think about tax havens the picture we see is usually of a small tropical island, its palm-lined colonial streets swarming with slick, shady lawyers and financiers who, for a fee, will happily hide money from spouses, creditors and the taxman. It’s an image that pervades our popular culture and one that Steven Soderbergh exploits to the max in his campy new film about the Panama Papers leak, The Laundromat.

Certainly, the fact that many Caribbean and other tropical islands in the Indian and Pacific oceans are tax havens—or better yet, paradis fiscaux in French—lends credence to this idea. But the reality is more complex and much closer to home than that. Tax havens come in all shapes and sizes, with webs that extend all around the world, entangling Canada’s financial, mining, and real estate markets, as examined later in this special issue of the Monitor.

After a short history of tax havens, including the key role Canadian banks and individuals have played in their establishment, this article explores how they have become a key part of the international corporate financial architecture, benefiting especially the wealthiest individuals and corporations in the world while harming the poorest. It then looks at how we can achieve positive changes, including through urgent measures the federal government could take to hold tax-dodgers to account and repatriate billions that could be put to better use serving public ends.

A very short history of tax havens

Switzerland was the first country to develop into a significant tax haven. Wealthy Europeans with money to hide were especially attracted by the historic financial secrecy laws of Swiss bankers, the country’s tradition of neutrality in wars, and a decentralized federal structure under which cantons (small self-governing regions) compete with each other for business.

Switzerland’s cantons flourished as international banking centres throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, but they did especially well during Europe’s devastating wars in the 20th century. Swiss neutrality made it possible for resident banks to lend and shelter money and wealth from all sides. The rise of income and wealth taxes in Western countries, originally to pay for these wars, made it even more attractive for the elite to hide their wealth in Switzerland.

Ordinary people were patriotically conscripted to fight and pay for Europe’s wars, but many of its wealthy, as always, found ways to elude both. They also weren’t prepared to let Swiss bankers take all the proceeds from the highly profitable business they had pioneered. City of London financiers developed their own web of offshore tax havens through the Channel Islands of Jersey and Guernsey and the Isle of Man, Crown dependencies that are not part of the United Kingdom.

During the 1930s, wealthy Americans and mobsters, including Meyer Lansky, used Switzerland, and islands closer to home including Newfoundland and Cuba, to both launder and hide their money from their governments. This helped them avoid the fate of Al Capone, who was famously convicted of tax evasion rather than the more violent crimes he was associated with. The Cuban revolution forced Lansky to move to the British colony of the Bahamas, which he helped develop into a more stable place to launder money and evade taxes.

Canadian banks and citizens were also intimately involved in the project to turn Caribbean countries including the Bahamas, Bermuda and the Cayman Islands into tax havens, as Alain Deneault documents so well in his book, Canada: A New Tax Haven. While these countries sported some political quasi-independence (though not so much to lose their cachet of stability under the British Crown), they increasingly became colonies of financial capital—a place for wealthy individuals and corporations from Western countries to hide their money and avoid taxes.

Part of the financial architecture

It’s important to understand that most tax havens didn’t develop on the margins of the financial centres of London, Toronto and New York, but as key parts of their respective international empires. They functioned similar to private clubs, with exclusive perks for the wealthy members, notably the power to avoid taxes and other obligations in their country, but without ever having to leave home. The government made moving funds back and forth even easier for these people by signing tax agreements and treaties with other known tax havens, and making it simple to establish shell corporations, trusts and foundations for the purpose of sheltering money.

Tax havens couldn’t exist without the very active facilitation and promotion of blue chip financial institutions including banks and accounting, legal and other firms. Very few wealthy individuals or corporations would take these risks without assurance that their assets would be safe and accessible, often only by them. Giant accounting firms including KPMG, EY, Deloitte and others are among the greatest promoters and facilitators of aggressive tax avoidance and use of tax havens.

Free trade agreements in the 1980s and ‘90s facilitated the globalization of industrial and financial supply chains. Tax havens provided multinational corporations straddling multiple countries with highly attractive opportunities to reduce their tax bills. It was easy to shift profits to low tax jurisdictions thanks to near century-old transfer pricing rules and arm’s length principles at the foundation of international tax rules.

The windfalls from international tax avoidance escalated as politicians engaged in mutual games of cutting corporate tax rates and making their regulations ever more friendly to foreign businesses, which were often offered better treatment than domestic firms. The creation of a European single market in the early 1990s and of stateless eurodollar markets provided far more possibilities to help multinational enterprises avoid taxes. So did the development of the modern corporate tax havens of Ireland, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. The information technology revolution and digitalization of the economy has taken tax avoidance to yet another dimension.

A whole universe of tax havens and low-tax jurisdictions now exists. Constellations of different tax havens service different major economies, the sources of their funds and strength of their links determined by different tax agreements between jurisdictions, their institutions, the players involved, and what each tax haven offers in terms of particular perks.

While wealthy individuals may just use one or two tax havens, corporations will establish subsidiaries in a number of different ones, with each serving a separate purpose. The multiplicity of tax havens further helps companies hide their assets and hedge their bets, in case political and public sentiment in one country turns the other way. And because the preferences provided by tax havens are generally always only available for foreign firms, having multinationals straddle many jurisdictions makes it easier for them to avoid taxes in all of them. For instance, at a time when it was the most valuable company in the world, Apple was able to transfer much of its wealth to subsidiaries that were not considered resident for tax purposes anywhere in the world, and to pay an effective tax rate of just 0.005%.

Tax me if you can

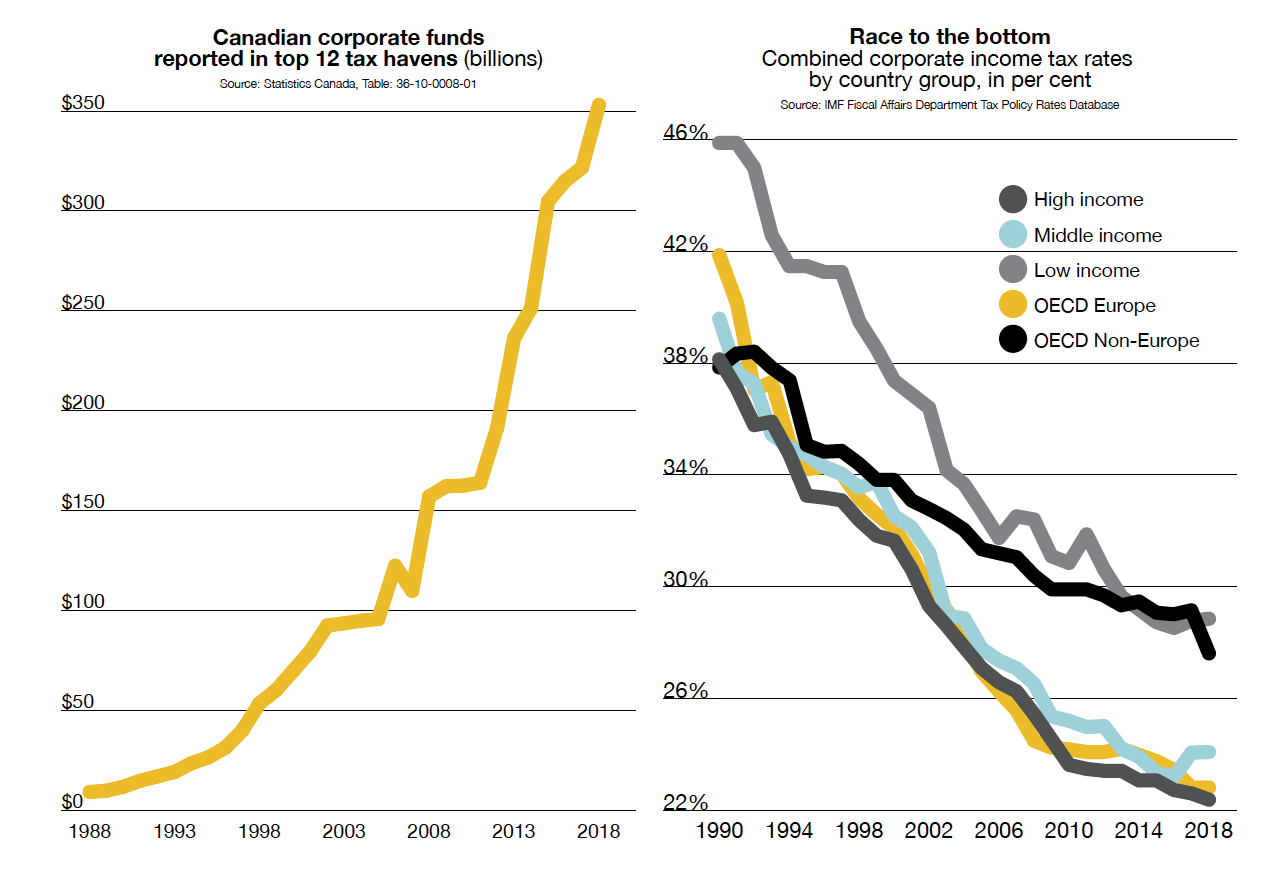

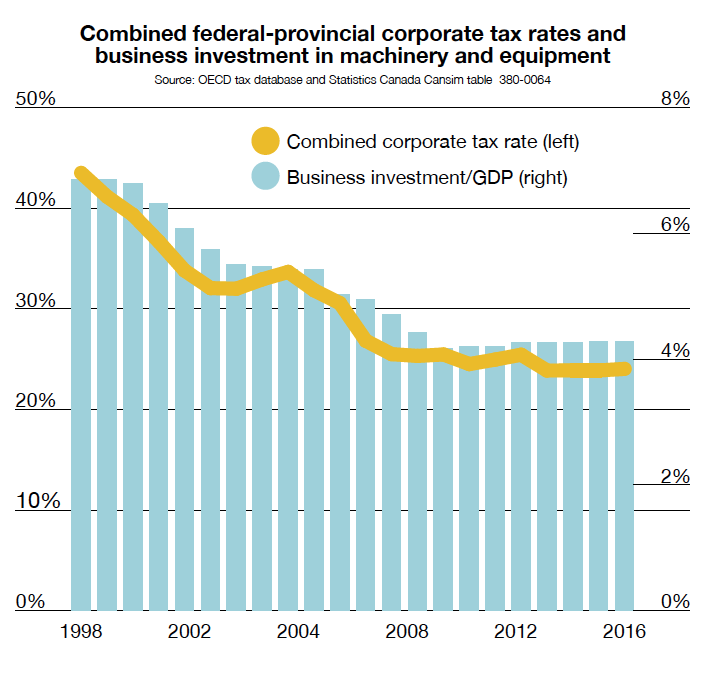

The expansion of tax havens has also helped drive down corporate tax rates around the world, as countries feel pressure to offer “competitive” business environments. Canada’s federal corporate tax rate has been slashed in half over the past two decades and other business taxes by more. But as in other countries, this race to the bottom on taxes in Canada has produced no significant increase in business investment.

Canada’s largest corporations have also been big users of tax havens. The Canadians for Tax Fairness publication Bay Street and Tax Havens reported that Canada’s 60 largest companies on the TSX60 Index had over 1,000 subsidiaries and related companies in tax havens, with some having over 50 each. Over 90% of Canada’s largest corporations had at least one subsidiary in a tax haven.

Large multinational enterprises in more traditional industries such as mining, oil and gas, manufacturing, construction, transportation, finance, pharmaceutical and retail have been able to avoid taxes for many decades using a variety of techniques. But the rapid expansion of corporations using digital platforms—Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Uber, AirBnB, etc.—has made international tax avoidance even more pervasive.

These corporations have much of their assets in software platforms, patents, brand names, and other forms of intellectual property that they can locate in different countries for the purpose of dodging taxes. In so doing, these mega-corporations have gained unfair advantages in comparison with smaller and medium-sized domestic competitors. International tax dodging has contributed to disturbing levels of corporate concentration and control in many different sectors, which has also reduced competition and is bad for the economy.

The chart on this page illustrates how rapidly Canadian corporations have increased their reported investments in corporate Canada’s top 12 tax havens—up to over $350 billion in 2018, representing over 27% of their total reported investment overseas. As these figures are just the officially reported numbers, the real amounts that Canadian corporations hold in tax havens are certainly higher. They are also only national level findings and don’t include assets in subnational tax havens such as Delaware, which is by far corporate Canada’s most popular overseas destination for establishing subsidiaries.

Recent analysis by the IMF revealed that “phantom investments” in empty shell corporations in tax havens have increased to an astonishing $15 trillion worldwide, representing 38% of all foreign direct investment overseas.

IMF researchers have also recently estimated that OECD countries lose an average of 1% of their GDP to this type of profit- and tax-shifting by large multinational corporations, adding up to over US$400 billion (C$530 billion) annually. For Canada, 1% of GDP would be equivalent to over $20 billion in revenues lost annually. That’s more than the federal deficit for this year, and an amount that could fund both free postsecondary tuition and a national pharmacare plan. Canada’s losses are probably lower than this, but even if they were half the amount it would still be a massive problem.

The losses are even more damaging for lower income countries. They lose over US$200 billion ($C265 billion) in revenues annually from corporate profit- and tax-shifting through tax havens, equivalent to over 1.3% of their GDP and more than they receive in international development assistance annually. These countries depend proportionally more on corporate taxes for their public revenues because their populations are poorer. They also have less capacity to investigate, audit, battle and recover taxes from multinational corporations. The lack of revenue in these countries to improve health care, public services and education is literally a life-and-death problem.

This is why international development organizations such as Oxfam, Action Aid, Save the Children, Inter Pares and others have been at the forefront of tax justice movements around the world. They’ve seen that the primary beneficiaries of tax havens and our archaic international corporate tax rules have been the wealthiest individuals and the largest multinational corporations, while it is the poorest who have been hurt the most.

It has taken decades of advocacy and fighting by small tax justice organizations—including the Tax Justice Network, the Global Alliance for Tax Justice, Canadians for Tax Justice and Echec aux Paradis Fiscaux, labour unions and other supporters—to bring attention to the magnitude and injustice of this problem. But international organizations like the OECD, IMF, G20 and national governments are finally paying attention and pledging to make substantial reforms. The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) has also had a big impact with the enormous amount of work their journalists have done analyzing millions of files from the Panama Papers, Paradise Papers and other leaks of information from tax havens.

Urgent reform needed

As a result of public pressure, national governments at the 2012 G20 summit asked the OECD to draw up a base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) action plan to help prevent multinational corporations from avoiding tax by shifting profits to tax havens and low-tax jurisdictions. The first BEPS action plan, launched in 2015, significantly included reforms to increase transparency about what multinational corporations actually pay in tax, allow automatic sharing of tax information, and plug a few holes in tax treaties. But the OECD plan failed to fundamentally reform the international corporate tax system.

As a result, a number of OECD member countries were pressured by the public to introduce their own specific taxes on multinational corporations, often targeted at digital and e-commerce giants such as Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon and others, which have been particularly adept at avoiding taxes.

For instance, Australia introduced a multinational anti-avoidance law two years ago that allows the government to apply a more punitive 40% diverted profits tax on multinationals that are deemed to have aggressively avoided taxes. Britain will start applying a digital services tax in April 2020 that applies to the revenues of large digital corporations associated with their U.K. users. France has also committed to introducing a tax of 3% on the French revenues of digital giants like Facebook, Apple and Google. Meanwhile, the United States even introduced special anti-avoidance taxes on multinational corporations as part of a major tax reform bill in 2018.

All these different measures helped forced the international community to take action or risk creating a highly balkanized, varied and unpredictable international corporate tax system. In just the past year, the OECD and IMF have agreed that significant reform is needed. As Christine Lagarde, the head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), recently stated:

The current international corporate tax architecture is fundamentally out of date [because] the ease with which multinationals seem able to avoid tax, combined with the three-decade long decline in corporate tax rates, undermines both tax revenue and faith in the fairness of the overall tax system…. The current situation is especially harmful to low-income countries, depriving them of much-needed revenue to help them achieve higher economic growth, reduce poverty, and meet the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals.

G20 and G7 leaders have agreed to try and achieve a consensus solution by the end of 2020. It’s a very ambitious target given how long the existing international corporate tax system has been in place. The ideas on the table could represent the most significant changes to that system in a century.

A majority of countries appear to agree there needs to be a minimum international effective corporate tax rate. But there’s disagreement about what this should be, whether it should apply to all or just “residual” profits, and many other technical but important factors. There also appears to be broad agreement that multinationals should be treated as unitary enterprises instead of being able to shift their profits to affiliated companies with impunity.

A number of Western nations are pushing to keep the existing transfer pricing system for the “routine profits” of multinational corporations, but to introduce new additional taxes for the higher-than-routine “residual profits” of larger, more profitable multinationals. However, doing this would retain a broken and ineffective system that allows corporations to avoid taxes. It would also make the international tax system even more complicated and open to dispute over what constitutes routine and residual profits.

A proposal from India and the G24 group of nations—also supported by tax justice organizations including the Tax Justice Network and the Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation—would deliver the much more substantial reform that is needed. Under the proposal, multinational enterprises would be required to pay tax to the different countries they operate in using a formula that apportions their profit according to the share of real economic factors in each country, such as sales, employment and assets.

In Canada and the United States, corporations have been required to apportion their profit for tax purposes between provinces (or states) in this way for over 50 years. If this type of system was also in place internationally, revenues from corporate taxes would be higher by an estimated $10 billion or more per year.

Much is at stake in these international tax reform discussions: hundreds of billions of dollars in revenues could be repatriated if they get it right. It is very encouraging that the reforms long proposed by tax justice activists are now being very seriously considered by the OECD, IMF and national governments. But we should be under no illusions about the power of the corporate forces that will resist these progressive changes.

One problem is that these discussions are being led by the OECD, essentially a club of wealthy nations. Though other countries can have a seat at the table through its “inclusive framework” process, they aren’t necessarily equal partners and have less capacity to analyze and engage. Ideally, these types of international negotiations should occur at the United Nations, but it doesn’t have the capacity in this area and has been made less functional by the U.S. Trump administration and others in recent years.

There’s still a chance the talks will achieve historic positive reform. Unfortunately, the Canadian government hasn’t yet appeared to want to play any significant role in this respect. Canada should strongly advocate for international adoption of a formulary apportionment system similar to the one we use successfully at home. It would be a win for the Canadian government, with the billions more in revenue it would gain, a win for Canadian businesses who will face less unfair competition, and a win for lower-income developing countries whose capacity to invest in sustainable development would be greatly enhanced.

The solutions

There’s no one silver bullet that will solve all the problems of international tax-dodging and tax havens. Instead, the federal government should take stronger action in the following areas:

- Stronger enforcement and harsher penalties to deter wealthy individuals and corporations from engaging in international tax evasion, and others from promoting the practice.

- Prosecute the professional promoters of tax evasion schemes, including lawyers and accounting firms such as KPMG.

- Increase funding to the Canada Revenue Agency and prosecution service so that it can investigate and shut down sophisticated tax- avoidance and evasion schemes.

- Restrict corporations or consortiums that engage in tax evasion and aggressive international tax avoidance from obtaining federal government contracts.

- Change Canadian tax laws and international tax rules to force international corporations to pay their fair share of tax by:

- introducing a minimum international corporate tax rate;

- treating multinational enterprises as single entities for tax purposes so they can’t avoid taxes through subsidiaries and affiliated companies;

- apportioning the profits of multinational corporations between countries based on real economic factors, such as sales and employment, so they can’t avoid taxes by shifting profits to tax havens;

- strengthening rules to prevent other common forms of tax avoidance and evasion;

ending double non-taxation agreements with tax havens, requiring corporations and wealthy individuals to pay reasonable minimum rates of tax; and - requiring large multinational corporations to publish financial reports, including taxes paid, on a country-by-country basis.

Toby Sanger is Director of Canadians for Tax Fairness. He previously worked as Senior Economist of the Canadian Union of Public Employees, Chief Economist for the Yukon government and Principal Economic Policy Advisor to the Ontario Minister of Finance.